Attachment theory is based on the idea that we learn whether the world is a safe place during the first three years of our lives. That it is during those years that we figure out if and how much we can trust other people. That our relationships with our “primary attachment figures” – typically our parents – during the first 1000 or so days of our lives, form the basis for our emotionally intimate relationships later in life.

Attachment theory is based on the idea that we learn whether the world is a safe place during the first three years of our lives. That it is during those years that we figure out if and how much we can trust other people. That our relationships with our “primary attachment figures” – typically our parents – during the first 1000 or so days of our lives, form the basis for our emotionally intimate relationships later in life.

The theory was originally developed by John Bowlby (1907 – 1990), a British psychoanalyst who wanted to understand the intense distress he saw in infants separated from their parents. Bowlby observed that separated infants would go to great lengths (e.g., crying, clinging, frantically searching) to prevent separation from their parents or to reestablish closeness to a missing parent. At the time, psychoanalysts believed that these behaviors were immature defense mechanisms operating to repress emotional pain. Bowlby noted, though, that these behaviors are seen in many other mammals, and speculated that these behaviors may have had a survival function earlier in our evolution.

The theory was originally developed by John Bowlby (1907 – 1990), a British psychoanalyst who wanted to understand the intense distress he saw in infants separated from their parents. Bowlby observed that separated infants would go to great lengths (e.g., crying, clinging, frantically searching) to prevent separation from their parents or to reestablish closeness to a missing parent. At the time, psychoanalysts believed that these behaviors were immature defense mechanisms operating to repress emotional pain. Bowlby noted, though, that these behaviors are seen in many other mammals, and speculated that these behaviors may have had a survival function earlier in our evolution.

Bowlby believed that these attachment behaviors, such as crying and searching, were adaptive responses to separation from a primary attachment figure–someone who provides support, protection, and care. Because human infants cannot feed or protect themselves, they are dependent upon the care and protection of adults. Bowlby argued that infants who were able to use these behaviors to stay close to an attachment figure via would have been more likely to survive and reproduce. What Bowlby called the “attachment behavioral system” was gradually “designed” by natural selection to ensure closeness to an attachment figure.

The attachment behavior system essentially asks “Is the attachment figure nearby, accessible, and attentive.” If the child feels the answer to this question to be “yes,” he or she feels loved, secure, and confident, and, behaviorally, is likely to explore his or her environment, play with others, and be sociable. If, however, the child perceives the answer to be “no,” the she or he experiences anxiety and is likely to exhibit attachment behaviors ranging from simple visual searching on the low extreme to active following and vocal signaling on the other. These behaviors continue until either the child can reestablish a desirable level of physical or psychological proximity to the attachment figure, or until the child “wears down,” as may happen after a prolonged separation or loss. In such cases, Bowlby believed that young children experienced profound despair and depression.

The other researcher most commonly associated with Attachment Theory is Mary Ainsworth (1913-1999). The developer of “the strange situation procedure,” the most common and empirically supported method for assessing attachment in infants, she was the 97th most cited psychologist of the 20th century. Many of Ainsworth’s studies are “cornerstones” of modern-day attachment theory

The other researcher most commonly associated with Attachment Theory is Mary Ainsworth (1913-1999). The developer of “the strange situation procedure,” the most common and empirically supported method for assessing attachment in infants, she was the 97th most cited psychologist of the 20th century. Many of Ainsworth’s studies are “cornerstones” of modern-day attachment theory

Adult Attachment Styles

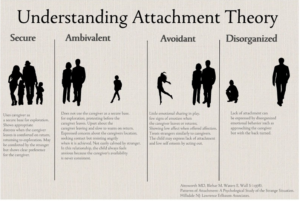

Secure

Securely attached people (59% of adults, per one large nationally representative study) tend to agree with the following statements: “It is relatively easy for me to become emotionally close to others. I am comfortable depending on others and having others depend on me. I don’t worry about being alone or others not accepting me.” This style of attachment usually results from a history of warm and responsive interactions with their attachment figures in the early years of their lives. Securely attached people tend to have positive views of themselves and their attachments. They also tend to have positive views of their relationships. They typically report greater satisfaction and adjustment in their relationships than people with other attachment styles. Securely attached people feel comfortable both with intimacy and with independence.

Secure attachment and adaptive functioning are promoted by a caregiver who is emotionally available and appropriately responsive to his or her child’s attachment behavior, as well as capable of regulating both his or her positive and negative emotions.

Insecure

Anxious-preoccupied

People with anxious-preoccupied attachment type (11% or American adults) tend to agree with the following statements: “I want to be completely emotionally intimate with others, but I often find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like“, and “I am uncomfortable being without close relationships, but I sometimes worry that others don’t value me as much as I value them.” People with this style of attachment seek high levels of intimacy, approval, and responsiveness from their attachment figure. They sometimes value intimacy to such an extent that they become overly dependent on the attachment figure. Compared with securely attached people, people who are anxious or preoccupied with attachment tend to have less positive views about themselves. They may feel a sense of anxiousness that only recedes when in contact with the attachment figure. They often doubt their worth as a person and blame themselves for the attachment figure’s lack of responsiveness. People who are anxious or preoccupied with attachment may exhibit high levels of emotional expressiveness, emotional dysregulation, worry, and impulsiveness in their relationships.

Dismissive-avoidant

People with a dismissive style of avoidant attachment tend to agree with these statements: “I am comfortable without close emotional relationships”, “It is important to me to feel independent and self-sufficient”, and “I prefer not to depend on others or have others depend on me.” People with this attachment style desire a high level of independence. The desire for independence often appears as an attempt to avoid attachment altogether. They view themselves as self-sufficient and invulnerable to feelings associated with being closely attached to others. They often deny needing close relationships. Some may even view close relationships as relatively unimportant. Not surprisingly, they seek less intimacy with attachments, whom they often view less positively than they view themselves. People with a dismissive-avoidant attachment style tend to suppress and hide their feelings, and they tend to deal with rejection by distancing themselves from the sources of rejection (e.g. their attachments or relationships).

People with a dismissive style of avoidant attachment tend to agree with these statements: “I am comfortable without close emotional relationships”, “It is important to me to feel independent and self-sufficient”, and “I prefer not to depend on others or have others depend on me.” People with this attachment style desire a high level of independence. The desire for independence often appears as an attempt to avoid attachment altogether. They view themselves as self-sufficient and invulnerable to feelings associated with being closely attached to others. They often deny needing close relationships. Some may even view close relationships as relatively unimportant. Not surprisingly, they seek less intimacy with attachments, whom they often view less positively than they view themselves. People with a dismissive-avoidant attachment style tend to suppress and hide their feelings, and they tend to deal with rejection by distancing themselves from the sources of rejection (e.g. their attachments or relationships).

Fearful-avoidant

People with losses or other trauma, such as sexual abuse in childhood and adolescence may develop this type of attachment and tend to agree with the following statements: “I am somewhat uncomfortable getting close to others. I want emotionally close relationships, but I find it difficult to trust others completely, or to depend on them. I sometimes worry that I will be hurt if I allow myself to become too close to other people.” They tend to feel uncomfortable with emotional closeness, and the mixed feelings are combined with sometimes unconscious, negative views about themselves and their attachments. They commonly view themselves as unworthy of responsiveness from their attachments, and they don’t trust the intentions of their attachments. Similar to the dismissive-avoidant attachment style, people with a fearful-avoidant attachment style seek less intimacy from attachments and frequently suppress and deny their feelings. Because of this, they are much less comfortable expressing affection.